IP Alerts

August 4, 2015

As discussed in an earlier alert, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has been making efforts to train examiners on, clarify, and revise the issued 2014 Interim Guidance on Patent Subject Matter Eligibility. These efforts have led to the recently published July 2015 Update: Subject Matter Eligibility. The July 2015 Update provides further clarification on how examiners should apply the procedures detailed in the 2014 Guidance. While the July 2015 Update does not alter the two-part test to be used by examiners in determining eligibility under section 101, it does provide clarification on how examiners are to identify an abstract idea and the evidence that must be presented by examiners in establishing ineligibility under section 101.

A primary concern in determining eligibility under section 101 is guarding against attempts to monopolize laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas. As noted by the U.S. Supreme Court in Diamond v. Chakrabarty, these are to be “free to all men and reserved exclusively to none.” Yet the Supreme Court also stated in Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Labs, Inc. that “all inventions at some level embody, use, reflect, rest upon, or apply laws of nature, natural phenomena, or abstract ideas.” Consequently, by its very nature, a patent claim will monopolize a certain application of an abstract idea, law of nature, or natural phenomena.

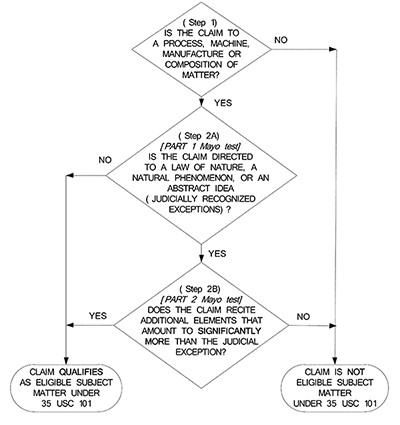

As set forth in the 2014 Guidance, when determining if a claim presents a patent-eligible invention under section 101, USPTO examiners are to use the flowchart below, which the USPTO believes to be consistent with the Supreme Court’s decision in Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int’l.

As the chart indicates, the examiners are first to determine if the claim is directed to one of the four permitted statutory classes (process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter). If so, the examiner is then to determine if the claim is directed to an abstract idea or other judicially recognized exception.

As stated in the 2014 Guidance, a claim should be considered directed to an abstract idea only if an abstract idea is recited in at least one of the claim’s limitations. The July 2015 Update provides further guidance on how examiners are to identify abstract ideas to “ensure that a claimed concept is not identified as an abstract idea unless it is similar to at least one concept that the courts have identified as an abstract idea.” In other words, the July 2015 Update clarifies that it is the courts, and not examiners, that get to make the call as to whether or not something is an abstract idea. Examiners are to just determine if the claims are directed to—that is, recite—one of the categories of abstract ideas previously identified by the courts.

To aid in this determination, the July 2015 Update defines four categories of abstract ideas:

A. “Fundamental economic practices,” which are foundational and basic concepts relating to the economy and commerce, such as agreements;

B. “Certain methods of organizing human activity,” which are concepts relating to interpersonal and intrapersonal activities;

C. “An idea ‘of itself,'” which are mental processes that can be performed in the human mind or on paper and ideas standing alone, such as concepts, schemes and plans; and

D. “Mathematical relationships/formulas,” which are mathematical concepts including algorithms, relationships, formulas, and calculations.

Examiners have the initial burden “to explain why a claim or claims are unpatentable clearly and specifically, so that applicant has sufficient notice and is able to effectively respond.” The examiner must provide a reasoned rationale identifying the abstract idea recited in the claim and why it fits within one of the above categories. When an examiner satisfies this initial burden, he or she has established a prima facie case of ineligibility under section 101.

If the examiner determines that the claim in question does contain a properly identified abstract idea, then the examiner is to determine if the claim contains “significantly more” than the abstract idea. The 2014 Guidance explains that in making this determination, the examiner is to ascertain whether the claim recites anything more than what is routine and conventional. The July 2015 Update directs that this determination is not be based solely on the elements of the claim considered individually but in combination. Accordingly, a claim may contain “significantly more” when the elements considered in combination amount to something more than what is routine and conventional, even though each limitation in isolation is routine and conventional. If something more than routine and conventional processes or components are recited in the claim, then the claim should not be rejected under section 101.

If, on the other hand, nothing more than what is routine and conventional is recited in the claim, then the examiner must determine if the claimed invention improves a technology or field of technology, as discussed in DDR Holdings, LLC v. Hotels.com, L.P. If so, then the claim should not be rejected under section 101.

Determinations as to whether something is “significantly more” than what is routine and conventional, according to the July 2015 Update, can be made based on the examiner’s own knowledge of the relevant technical field. Characterizing the decisions of the courts in recent cases as not relying on evidence and being resolved without any factual findings, the July 2015 Update states the determination of patent eligibility under section 101 is a question of law. In so doing, the July 2015 Update allows an examiner to rely on his or her own expertise in the art to determine if the claims contains “significantly more.”

It remains to be determined if the USPTO’s methodology will be approved by the courts. To some extent there is tension between an examiner’s ability to rely on his or her own expertise and the holdings of certain prior court decisions. For example, the Supreme Court held in Dickinson v. Zurko that the USPTO must present a particular evidentiary record adequate to support its conclusion of unpatentability when making a claim rejection.

--Written by Fitch Even attorney James A. Zak

Fitch Even IP Alert®